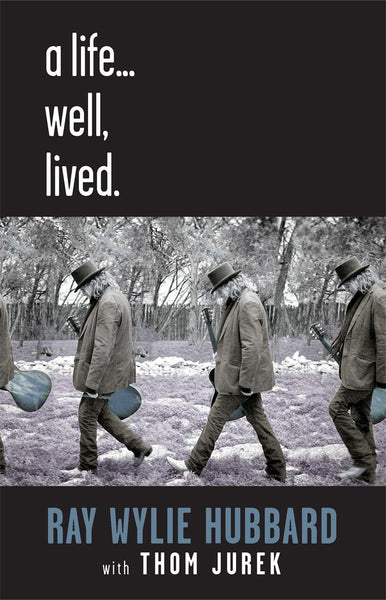

A Life...Well, Lived - Ray Wylie Hubbard Autobiography

A Life...Well, Lived - Ray Wylie Hubbard Autobiography

$25.00 USD

was

WIMBERLEY, Texas — As a general rule, Ray Wylie Hubbard doesn’t really cater to nostalgia. Although he’s been credited (or blamed, as he’s prone to put it dryly) for penning one of the defining anthems of the entire 1970s progressive country movement, the Oklahoma-born, Texas-reared living legend has spent the last quarter century in constant pursuit of new artistic vistas and challenges, reinventing and redefining his musical identity every step of the way. Always a generous performer, he’ll still serve up that “obligatory encore” (all together now: “And it’s up against the wall, REDNECK MOTHER!”) with characteristic good humor, but he certainly hasn’t earned his laurels as one of the most respected artists in modern Americana — not to mention in the storied pantheon of Texas poet troubadours — by living in the past.

Over the course of a dozen acclaimed albums going back to his early ’90s comeback, he has distinguished himself time and again as both a songwriter’s songwriter par excellence and as one of the gnarliest, grittiest Texas groovers this side of Lightnin’ Hopkins. Case in point: This year’s The Ruffian’s Misfortune, a record praised by American Songwriter as “a lean, mean set that wraps up in just over a half hour but whose raw reverberations last long after.”

Over the course of a dozen acclaimed albums going back to his early ’90s comeback, he has distinguished himself time and again as both a songwriter’s songwriter par excellence and as one of the gnarliest, grittiest Texas groovers this side of Lightnin’ Hopkins. Case in point: This year’s The Ruffian’s Misfortune, a record praised by American Songwriter as “a lean, mean set that wraps up in just over a half hour but whose raw reverberations last long after.”

All of which just begs the question: Considering he’s still raising the bar and releasing the best music of his life at age 69, what in the world could have possibly provoked Hubbard to lay down his beloved guitar long enough to not just reflect back on his past, but to actually commit it to page for his first memoir, A Life ... Well, Lived (out Nov. 2 on Bordello Records, the label Ray Wylie and his wife and manager, Judy Hubbard, launched five years ago)? Chalk it all up to a whim — and the persistent prodding of a good friend, music writer (AllMusic.com) Thom Jurek.

“We were emailing, and I wrote him some story about when Willie Nelson kidnapped me,” says Hubbard, briefly recounting a night somewhere back in his “honky-tonk fog” days when Willie Nelson’s road manager Poodie Locke and drummer Paul English pounded on his Dallas door at 3 a.m. and abducted him for a bus run up to Milwaukee for a beer festival. They didn’t even give Hubbard time to pack a bag; English told him he could “borrow Willie’s toothbrush.”

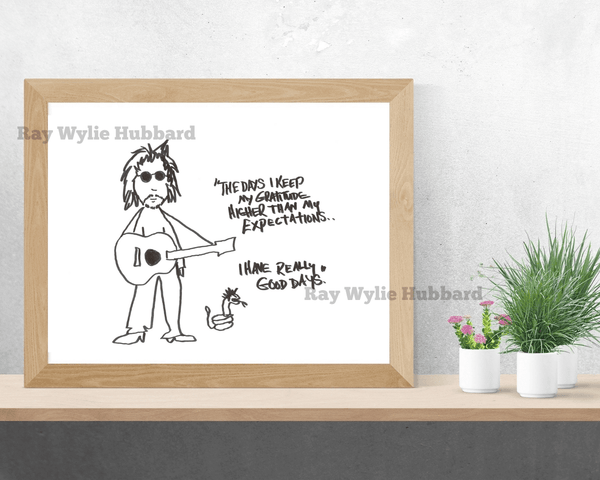

When Jurek wrote back telling him how funny the story was — not to mention “pretty well written” — Hubbard fired off another one, about the time he saw Muddy Waters when he was 19. Next thing Hubbard knew, he was sharing similar stories — some old, some new, some not so much stories as just random (but still funny and/or insightful) stream-of-conscious musings from the road — on Facebook, much to the delight of his 80,000+ followers. By the time Jurek poked him with a subtle “You know, you oughta write a book ...,” Hubbard was already well on his way.

“It just kind of fell into place,” Hubbard explains, noting that the whole book took him the better part of two years to complete, with Jurek earning a “with” credit on the cover for his invaluable input not just as editor but as a sounding board and cheerleader. “I wrote every word in it, and I don’t think he really changed anything at all,” Hubbard continues, “but I don’t think I would have finished it without his encouragement, which is why I wanted to give him more than just an ‘edited by’ credit.”

Chief among Jurek’s suggestions early on was the book’s unique formatting, with “regular” chapters — for what Hubbard calls “the real autobiography stuff” — alternating with mini “road stories” vignettes composed in Hubbard’s signature Facebook posting style of free-form stream of consciousness with minimal regard to strict punctuation and no regard whatsoever to capitalization. Some of those mini vignettes play off of the adjoining main chapters like lyrical refrains (much like the accompanying lyrics to several of his songs sprinkled throughout the book); others flash forward decades into the more recent “present” to offer glimpses of Hubbard’s dramatic career resurgence over the last decade, from making his debut on the Late Show With David Letterman at age 66 to being invited onstage at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles to sing “Help From My Friends” with “a f***** Beatle” (Ringo Starr, who’s been a Hubbard fan ever since hearing the latter’s 2006 album, Snake Farm).

As entertaining as the road stories are, though, the main narrative proves every bit as colorful, tracing Hubbard’s life’s journey from early childhood in Southern Oklahoma, through adolescence in Dallas, his earliest performances as part of the folk trio Three Faces West in Red River, N.M., and all the way through his white knuckle ride (fueled by more than a little white powder) through the progressive/outlaw/Texas country boom of ’70s. That was the golden age of post-Nashville Willie, Jerry Jeff Walker and Michael Martin Murphey, among others, with major-label record deals to go around for everybody. That included Ray Wylie Hubbard and the Cowboy Twinkies, a scrappy band of folk, blues and psychedelia-reared country rockers that could veer from Merle Haggard to Led Zeppelin on a dime. But sessions for Atlantic Records quickly hit the skids and a second shot at the big time with Warner Reprise brought the whole band to tears when the label slathered their debut with female backing vocals. After that, the rest of Hubbard’s trip through the ’70s and ’80s reads like a Texas-themed Spinal Tap, culminating in a rock-bottom residency playing happy hour sets between lingerie shows at a sleazy lounge near the airport. Throw in divorce, deep depression over the death of his father, festering doubts about his songwriting and guitar playing chops and an escalating slide into full-bore alcoholism, and you’ve got all the makings of a classic music business cautionary tale.

Spoiler alert: The book doesn’t end that way. Right about the halfway mark, Hubbard wakes up on the morning of his 41st birthday, gives up alcohol and drugs cold turkey and follows the advice of a newly clean, sober, and rejuvenated Stevie Ray Vaughan in a commitment to the long road to recovery. “There ain’t no elevators,” Stevie tells him at the outset, “you got to take the steps.” Along the way, an initially deeply skeptical Hubbard finds God, a soul mate in the aforementioned Judy, and ultimately a new lease on both his career and his artistic self confidence by swallowing his pride, signing up for fingerpicking lessons at age 42 and immediately writing the best song of his life, “The Messenger.” From that point on, he begins making the kind of records he doesn’t feel the need to make excuses for — especially after he adds slide guitar to his repertoire and reallyfinds his groove. Ray and Judy get married, move to a little town called Wimberley nestled deep in the Texas Hill Country south of Austin, and raise a gifted son named Lucas who ends up playing lead guitar in his dad’s band on both Jimmy Fallon and Letterman before his 20th birthday.

It’s quite a life, all right, and a damn fine story to boot, even in summary. But it’s the lively, personable prose and Hubbard’s inimitable voice that really makes A Life ... Well, Lived both sing and howl. As anyone who’s ever had the good fortune of seeing Ray Wylie perform can attest, his impeccable timing and wry, self-deprecating stage banter is worth the price of admission on its own, and that natural comedic flair is brought into even sharper relief on the page. Of course, there’s plenty of that wit weaved right into many of the song lyrics collected here, too, along with profundity and poetic beauty in spades that will read as revelatory to diehard fans of his music as it will to Hubbard neophytes.

And best of all — at least by Hubbard’s own modest appraisal — it all fits inside a tidy little package that feels, well ... not unlike his Ruffian’s Misfortune album from earlier this year, positively lean and mean.

“I really like the size of it, that it seems small,” he says of his tome’s svelte 174 pages (including the terrific afterword penned by Judy). Although Hubbard’s a voracious reader and an avowed Stones fan, he admits he found the sheer heft of Keith Richards’ own Life a tad imposing. “But Dylan’s Chronicles, on the other hand — that’s a great size and what I aimed for. I didn’t want to pad it just for the sake of padding it; I wanted to get in there, get to the punchline, and get to the next chapter. So it feels like a real book, but it’s ... you know, portable.

“And,” he continues, waiting a perfect beat to land his pitch, “there’s pictures in it!”